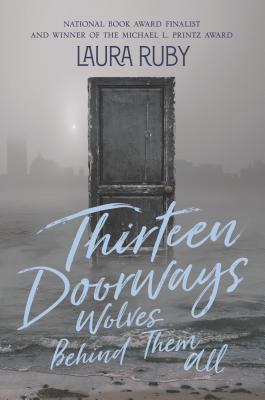

When their mother dies, Frankie and her siblings are sent to an orphanage until their Italian  immigrant father can pull himself together and provide for them in Thirteen Doorways, Wolves Behind Them All (Balzer & Bray 2019) by Laura Ruby. Set in late Depression era in Chicago, we see all of society struggling in this National Book Award finalist. Now here’s the kicker. The narrator is a deceased young woman—a ghost—who is able to see what just about everyone and anyone is doing—or thinking.

immigrant father can pull himself together and provide for them in Thirteen Doorways, Wolves Behind Them All (Balzer & Bray 2019) by Laura Ruby. Set in late Depression era in Chicago, we see all of society struggling in this National Book Award finalist. Now here’s the kicker. The narrator is a deceased young woman—a ghost—who is able to see what just about everyone and anyone is doing—or thinking.

The writing is lyrical only when it needs to be—such as the opening. Likening her to an abalone cup, the narrating ghost says, “Frankie traced the pearlescent edge of the shell with her finger,” observes that it still wasn’t broken, and neither was Frankie. Then Frankie hears a fox cry in the distance. If I weren’t already hooked by the ghost-narrator, the mystery, wildness, and subtle delicacy would draw me right in.

The orphanage is Catholic which plays heavily into the story. Frankie, curious about her young womanhood, irritates many of the nuns, who, out of fear, behave cruelly to their pubescent charges. Or maybe they’re cruel for some other reason. Sister George, wakes many a girl by hefting her mattress and spilling her to the floor. Daily.

But nothing is going to keep Frankie down—not even her annoying younger sister Toni. Not until her father arrives with a meatball sandwich for his four children, and a new wife and her children in tow. He announces that he will take her older brothers and his new family to Colorado where he will start anew as a cobbler for miners—leaving Frankie and Toni behind. There’s a promise to fetch them, but years pass, Frankie falls in love, her young soldier marches off to World War II, and when will her father return for them? But maybe the orphanage is a safer place to grow up than in her family home, where she appears to be worthless enough to be discarded.

The other story is that of the narrator Pearl who we eventually discover died during World War I. Both Frankie and Pearl’s stories are mysteries, which come together at the end in a surprising way.

Perhaps one of my favorite aspects of this admirable book is that it comes from the life and stories of the author’s late mother-in-law, Frances Ponzo Metro. This you find out in the end-matter. Metro told her stories in snippets and out of order to the fascinated author, surprised that anyone would be interested. And Ruby did copious research, interviewing Metro’s fellow orphans, viewing archival documents and films of Angel Guardian (the German Catholic orphanage in Chicago), as well as copious reading about the Depression, World Wars I and II.

This is another wonderful cross-over book for adults and young adults.

Patricia Hruby Powell is the author of the award-winning Josephine; Loving vs Virginia; and Struttin’ With Some Barbecue among others. She teaches writing classes at Parkland College. talesforallages.com