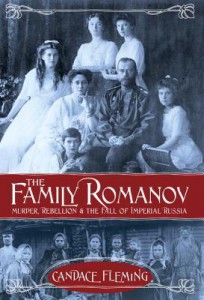

Candace Fleming’s “The Family Romanov: Murder, Rebellion & the Fall of Imperial Russia” (Schwartz & Wade 2014) centers on the imperial family,  telling the complex Russian history through the eyes of both nobility and peasantry.

telling the complex Russian history through the eyes of both nobility and peasantry.

In 1903 Russian nobility represented only 1.5 percent of the population, but owned 90 percent of all Russia’s wealth. At the top of power pyramid, Tsar Nicholas II owned thirty palaces, estates in Finland, Poland, the Crimea, millions of acres of farmland, gold and silver mines, two private trains, artwork, five yachts, and jewels beyond belief. His income came from the taxation of his subjects.

Nicolas’ father, Tsar Alexander III, a bear of a man, scorned his son as a dunce and gave him no training for his future job, which would include ruling 130 million subjects on 1/6 the planet’s land surface in 34 provinces, choosing governors for each, and passing laws. Nicholas would be hiring and firing statesmen on a whim with “…flatterers telling him what he wanted rather than needed to hear.”

Before coming to power Nicholas married German princess, Alexandra. The two would have liked nothing better than to be left alone to raise their family. But rather than abdicate, the autocrat and his growing family, retreated to the country where Nicholas lost touch with Russia. Tsarina Alexandra, to the dismay of all Russians, took over a great deal of power. The two were utterly clueless to the plight of the peasants.

In interspersed chapters we hear the story of individual peasants whose major accomplishment was survival. They lived in filth, close quarters, were starving, oftentimes under the abuse of an otherwise powerless despotic peasant father.

Back at the country palace, Alexandra bore four girls—Olga, Tatiana, Maria, Anastasia—much to the chagrin of the people who needed a male heir to the throne. Finally a hemophiliac heir, Alexei, was born. He had two sailor nannies, whose job it was to catch him before he fell, bruised, and writhed in unimaginable agony for days, weeks, even months. There is still no cure for the disease. Alexandra knew she was a carrier, adored her children—especially her son—and was tortured by her son’s condition.

The famed Rasputin, a charlatan of a holy man, was the spiritual support of the royal couple. Several times the boy recovered just when Rasputin stepped in. Had the injury just run its course? The royal couple felt Rasputin had a direct link to God. After a brief period of popularity, Rasputin—detested by the Russians—was eventually assassinated.

Fleming makes sense of a chaotic history, taking us through Russia’s entry into WWI, Russia’s civil war, the rise of the Provisional Government, then the rise of the Bolsheviks and communism. In the end she walks us through the horrific execution of the Family Romanov—that which many of us may only have known through the confused eyes of Anastasia played by Ingrid Bergman in the 1956 film Anastasia.

What a page-turning, ambitious, well-written history Fleming has given us!

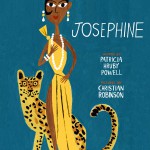

Patricia Hruby Powell’s new book Josephine: The Dazzling Life of Josephine Baker won a Boston Globe Horn Book 2014 Honor for Nonfiction and a Parents Choice Gold Award for Poetry.

freedom. In “The Port Chicago 50: Disaster, Mutiny, and the Fight for Civil Rights” (Roaring Brook 2014) Steve Sheinkin paints a picture of the segregated armed forces. Rather than being assigned to battle, blacks worked in the mess hall. Or worse.

freedom. In “The Port Chicago 50: Disaster, Mutiny, and the Fight for Civil Rights” (Roaring Brook 2014) Steve Sheinkin paints a picture of the segregated armed forces. Rather than being assigned to battle, blacks worked in the mess hall. Or worse. gave me about her stupendous new book, Josephine. You can read the interview here. http://inkrethink.blogspot.com/2014/03/josephine-rocks-and-so-does-her-author.html

gave me about her stupendous new book, Josephine. You can read the interview here. http://inkrethink.blogspot.com/2014/03/josephine-rocks-and-so-does-her-author.html

Here’s her entry:

Here’s her entry:  And then Beverly Patt who wrote the fascinating Best Friends Forever: A WWII Scrapbook, cleverly formatted as a scrap book. Here’s here entry:

And then Beverly Patt who wrote the fascinating Best Friends Forever: A WWII Scrapbook, cleverly formatted as a scrap book. Here’s here entry: I’ve just revised a razz-ma-tazz picture book biography, Struttin’ With Some Barbecue: Lil Hardin Armstrong about the jazz pianist and composer married to Louis Armstrong in the 1920s.

I’ve just revised a razz-ma-tazz picture book biography, Struttin’ With Some Barbecue: Lil Hardin Armstrong about the jazz pianist and composer married to Louis Armstrong in the 1920s. who served a bus full of black people at a roadside restaurant. Turned out it was Ella Fitzgerald and her band.

who served a bus full of black people at a roadside restaurant. Turned out it was Ella Fitzgerald and her band. Way Home and Dogs of Winter. I can’t wait to hear about her process.

Way Home and Dogs of Winter. I can’t wait to hear about her process. Stage: A Novel in 5 Acts. Terrific. I love all her books, the latest being Mumbet’s Declaration of Independence. Get a preview here http://www.gretchenwoelfle.com/all_the_world_s_a_stage__a_novel_in_five_acts_113204.htm

Stage: A Novel in 5 Acts. Terrific. I love all her books, the latest being Mumbet’s Declaration of Independence. Get a preview here http://www.gretchenwoelfle.com/all_the_world_s_a_stage__a_novel_in_five_acts_113204.htm Scandinavian folktales. Superstitions are alive and alluring—with the invisible and wicked huldrefolks lurking near cradles and under bridges.

Scandinavian folktales. Superstitions are alive and alluring—with the invisible and wicked huldrefolks lurking near cradles and under bridges. Lockhart, but her actual story begins “summer fifteen” when she is 15. The blueblood Sinclair family own Beechwood Island and all converge there every summer. Her grandparents reign in one mansion and their three middle-aged daughters squabble over the other three island mansions.

Lockhart, but her actual story begins “summer fifteen” when she is 15. The blueblood Sinclair family own Beechwood Island and all converge there every summer. Her grandparents reign in one mansion and their three middle-aged daughters squabble over the other three island mansions.