Metaphors

A good metaphor makes my mind leap, flies me over a landscape, then, sets me down in a soft landing. Metaphors take “show-don’t-tell” to a higher level.

Consider Nina LaCour’s “We Are Okay” (Dutton 2017) (winner of the 2018 Printz Award for Excellence in Young Adult Literature). Marin, the protagonist says, “It was terrifying, the idea that we could fall asleep girls, minty breathed and nightgowned, and wake to find ourselves wolves.”

in Young Adult Literature). Marin, the protagonist says, “It was terrifying, the idea that we could fall asleep girls, minty breathed and nightgowned, and wake to find ourselves wolves.”

If this were a werewolf story, this line would be clunky—prosaic. But it’s not a werewolf story, it’s realistic fiction. One day we’re children, then we fall in love, discover our sexuality and we become something wild and dangerous. Wolves. What a mind-soaring metaphor!

One dictionary defines metaphor as “a figure of speech in which a word or phrase is applied to an object or action to which it is not literally applicable.”

There are famous frequently-quoted metaphors, such as Shakespeare’s, “All the world’s a stage,/ And all the men and women merely players./ They have their exits and their entrances . . .” from As You Like It. We enter at birth, play a child, a wife, a writer, a whatever, and then we exit in death. What kind of child? Writer? Whatever? It depends on your role. Because Shakespeare was a great thinker this is still a great observation of human life.

There are famous frequently-quoted metaphors, such as Shakespeare’s, “All the world’s a stage,/ And all the men and women merely players./ They have their exits and their entrances . . .” from As You Like It. We enter at birth, play a child, a wife, a writer, a whatever, and then we exit in death. What kind of child? Writer? Whatever? It depends on your role. Because Shakespeare was a great thinker this is still a great observation of human life.

Cliché or Dead Metaphors

There are cliché metaphors, such as “it’s raining cats and dogs.” Obvious advice would be, avoid those clichés. But that’s too simple. Speaking as a person who likes to bend rules, what if you have a character who speaks in lots of clichés because he’s annoying; or a character on the spectrum who is trying to make the non-literal more literal. She piles up metaphor clichés. That’s sort of fun. And funny. She says, “I’m the black sheep of the family. My brothers eat sausage but I eat kale.” “I tried to sneak out of the party, but I stepped in the ice bucket and got cold feet.” “My dad ate so many kettle chips, watching TV, that he turned into a couch potato.”

Or you could play with those cliché or “dead” metaphors and say, “it’s raining rats and frogs.” Or you could develop a gufus or simply hyper-creative character who gets clichés wrong and says, “I’m the purple sheep of the family.” “I got luke-warm feet.” My dad is a “couch rutabaga.” Old metaphors are fun to play with to develop characters or show a character’s quirkiness, creativity, or humor.

Sustained Metaphors

Not only can a metaphor be a word or a phrase, it can be sustained in an on-going passage. Lilli de Jong (Doubleday 2017) by Janet Benton is an adult book, but could definitely be read as a young adult novel. Besides which, the great Richard Peck (RIP) said “We write by the light of every story we have ever read.” You’ve heard it before: Read everything—in and out of your genre. Read the best.

by Janet Benton is an adult book, but could definitely be read as a young adult novel. Besides which, the great Richard Peck (RIP) said “We write by the light of every story we have ever read.” You’ve heard it before: Read everything—in and out of your genre. Read the best.

Anyway, Lilli (de Jong) is a young Quaker woman in 1890 Philadelphia who gets pregnant and is abandoned by her fiancé. She gives birth in a home for unwed mothers, and is pressured to give up her child and never look back. She says,

“I consider the lie that will underpin my own life. . . We each have our own version of that lie. It’s the currency with which we buy our return ticket to society.”

The lie is “currency.” That’s the metaphor. Then Lilli has an epiphany. She sees herself on the deck of a boat for which she has just purchased passage. A wave pulls her overboard. She can breathe underwater. She feels ecstatic. A lie would buy her passage into society, but when she’s washed overboard she envisions a different life path. This path has her consider keeping her child.

Several pages later, still speaking of the lie, it becomes a simile, first cousin to the metaphor. “The lies spread like a layer of lard beneath my skin.” More about similes in a moment, but can’t you just feel that lie under your skin—its greasy distasteful existence enveloping you?

A metaphor can carry a whole book as it does in my own Josephine: The Dazzling Life of Josephine Baker (Chronicle  2014). In fact an earlier title was “Vive la Volcano: Josephine Baker.” In the end, I kept the sustained metaphor, but not the title. On the first page, Josephine “erupted into the Roaring Twenties/—a VOLCANO.” When Josephine experienced rioters—whites against blacks—cross into her neighborhood . . .

2014). In fact an earlier title was “Vive la Volcano: Josephine Baker.” In the end, I kept the sustained metaphor, but not the title. On the first page, Josephine “erupted into the Roaring Twenties/—a VOLCANO.” When Josephine experienced rioters—whites against blacks—cross into her neighborhood . . .

Fear grasped hold of her heart

and squeezed tight

the core of a volcano.

Anger heated and boiled into steam,

pressing HOT

in a place DEEP IN HER SOUL.

Later she’d let the steam out

in little poofs.

POOF!

a funny face.

That used to be fear.

POOF!

She’d mock a gesture.

That used to be anger.

She’d turn it into a dance.

AH, VERY WITTY.

That volcano metaphor runs through the story. “Deep-trapped steam FLASHED and WHISTLED.” She slid like “BLACK LAVA.” “Sparks flew.” In earlier drafts, I’d used similes instead of metaphors, saying Josephine was like a volcano. But in a SCBWI workshop, editor Carolyn Yoder of Calkins Creek, suggested using metaphor to give the piece more muscle. She was right. (Going to workshops and receiving critiques is an important part of the learning process).

Similes

Using simile—a comparison of one kind of thing to another, using like or as—is pretty fun, too. I’ve often thought of  similes as slightly prosaic metaphors, but they can be powerful ways to “show.”

similes as slightly prosaic metaphors, but they can be powerful ways to “show.”

Sheila Turnage in her Newbery Honor book, Three Times Lucky (Dial 2012) has Mo say, “my stomach rolled like a dead carp.” Disgusting. Funny. Perfect. Or she describes a boy walking toward a pretty girl, “like he was sleep walking.” Can’t you see the smitten guy, too young to have learned to mask his desire, floating in puppy love? Many men never learn to mask their desire. Consider the hilarious Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine (Penguin 2017) by Gail Honeyman. About a 35 year old man, Eleanor says, “He couldn’t take his eyes off Laura, I noticed, apparently hypnotized rather in the manner of a mongoose before a snake.” “In the manner of” is the “like” or “as” in this simile.

In the picture book Free as a Bird: The Story of Malala by Lina Maslo (Balzer & Bray 2018), the title is a simile. In the story Malala’s father says, “Malala will be free as a bird!” This, of course, is the story of the Pakistani girl whose government forbade education for girls. After recovering from the attempt made on her life, Malala has spoken around the world for all girls (and boys) about their right to be educated. Her father’s wish for her daughter came true.  She is free as a bird.

She is free as a bird.

Similes are a great exercise to use in the classroom. One of the finest I’ve encountered was in a 4th grade classroom from a “naughty” boy. We were brainstorming on various similes. I requested a simile for, “The man is as bald as ____ .” A boy answers, “A light bulb.” Perfect. Not only is a light bulb fuzz-free, it’s shaped like a head. So it gives us a very accurate visual. Huzzah for the naughty boy. Of course, as light bulbs have become spirals, this particular simile has a limited shelf life or might have to be relegated to historical pieces—in the waning days when we use light bulbs shaped like heads.

Personification

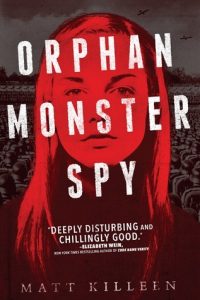

A personification is an implied metaphor—the attribution of a personal nature or human characteristic to something nonhuman—as is used in Matt Killeen’s Orphan Monster Spy (Viking 2018). In 1939 Germany, Sarah is a young blond Jewish girl spying in an elite Nazi girl’s school. Sarah speaks of her longed for safety and says, “Sarah seized on this longing and strangled it, squeezing its pitiful and pathetic neck. She was not safe.” This unattainable desire for safety  (non-human) is made human by giving it a neck that she must squeeze and strangle. Pretty cool.

(non-human) is made human by giving it a neck that she must squeeze and strangle. Pretty cool.

Emily Dickinson famously said, “If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry.” That’s how I feel about a great metaphor. And great similes. After all, metaphors, similes, personification are all poetic devices.

Stretch us in your writing. Take us somewhere new, somewhere we’ve never been before—and perhaps you the writer has never been before. I love it when a writer makes me see something that I’ve always known but never articulated. Metaphors can do that. Make your readers leap. Make them feel the top of their heads were taken off.

First published in The Prairie Wind, the newsletter of the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators, Illinois. https://illinois.scbwi.org/prairie-wind-2/

Leave a Reply