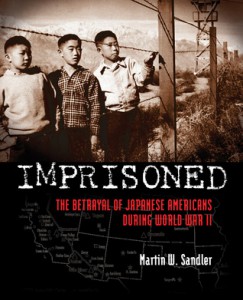

After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941, advisers told President Roosevelt that Japanese-Americans on the west coast were a threat to  U.S. security. Others said that was ridiculous. The threat-mongers won out and 120,000 loyal Americans of Japanese ancestry were evacuated and detained in remote areas of the U.S. for two years. So we are reminded in “Imprisoned: The Betrayal of Japanese Americans During World War II” by Martin W. Sandler (Walker 2013).

U.S. security. Others said that was ridiculous. The threat-mongers won out and 120,000 loyal Americans of Japanese ancestry were evacuated and detained in remote areas of the U.S. for two years. So we are reminded in “Imprisoned: The Betrayal of Japanese Americans During World War II” by Martin W. Sandler (Walker 2013).

Having as little as one out of sixteen Japanese great great grandparents—defined one as Japanese. These Americans had two weeks to pack, lease or sell businesses, merchandise, homes, or household goods. And white America took advantage offering the lowest prices.

In the first stage, in the holding areas, which were often racetrack stables, 25 people would be packed into a space, which would comfortably hold four people. There was no privacy. Sanitary conditions were deplorable and illness abounded—including dysentery, typhoid, and tuberculosis.

We learn that the generation born in Japan who immigrate to America are termed Issei. The next generation is Nisei, the next is Sansei. The Issei and Nisei in their “permanent” new internment camps planted trees, shrubs, creating tranquil Japanese gardens, all from salvaged scrap materials. “Our goal is the creation of an oasis.”

Others built chairs and tables from scrap wood or carved jewelry from found shells. They organized sports teams for basketball, football, ping pong, badminton, judo wrestling, and boxing. The biggest camp formed 100 baseball teams, and young children through 60 year olds competed in leagues. Education for both young and old was resumed. These are a resourceful people.

Young Japanese-American men were recruited from the camps to fight for the United States government, which had interned them. They fought fiercely to prove their loyalty. They won so many important battles in Italy and in France that they became the most decorated unit of their size. Ironically, the Japanese-American unit was one that liberated the first concentration camp for interned Jews—Dachau. Because army supplies were low they were ordered not to share their food rations. They did anyway and their officers turned a blind eye.

Even on their victorious return home, the west coast was riddled with “No Japs Wanted” signs and sentiments. Gaman is the Japanese cultural trait of continuing whatever the circumstance. And they did. These proud people when released from camps—their first amendment right having been profoundly violated—could not speak of the humiliation.

It wasn’t until the 70s when the Sansei, part of the rebellious generation, heard the stories and fought back for their parents. The U.S. government eventually apologized and made a small remuneration of $20,000 to each individual who had been interned in the camps.

This is a heartbreaking chapter in American history, but one people should be made aware of so that it cannot happen again. This sensitive insightful book is aimed for 7th graders and older.

Patricia Hruby Powell is a nationally touring speaker, dancer, author. Her new work Josephine: The Dazzling Life of Josephine Baker is available at book stores.

Leave a Reply