Writer’s Tips

CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT

by Patricia Hruby Powell

CONJURING, CHOOSING, OR CHECKING YOUR CHARACTER

The underlying object of reading is to have an emotional experience. Generally, we want our readers to experience the emotions that our characters feel—to empathize with our characters. So we as writers must do the work of developing characters our readers can love, be inspired by, laugh and cry with—whether we’re writers of fiction or nonfiction; whether we write picture books, middle grade, or young adult books. How is this done?

If you’re just thinking up a character, maybe you want to start with an issue. A problem. An external problem or obstacle; and an internal goal. For instance, an external obstacle of racism and poverty and an internal goal of wanting to dance.

Or maybe you’re midway through your story and need to think more deeply about your character. You might write more intuitively than analytically, as I do, but it might help to scrutinize your character in order to deepen that character on the page. Or to help you write your next character.

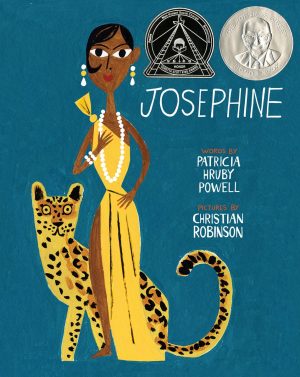

In the course of teaching writing I’ve had to analyze how to develop characters. Along the way, I’ve devised a template, incorporating my discoveries with the teachings of workshop leaders, writers of how-to-write books, and input from my wise editor Melissa Manlove, who analyzed the character development of Josephine, my biography of Josephine Baker, in order to educate me. Let’s look at these ten elements of character development. And note that it’s not easy to extract character development from plot, nor to cleanly divide each of these ten from the others, but for the sake of simplicity, I’m going to try.

the teachings of workshop leaders, writers of how-to-write books, and input from my wise editor Melissa Manlove, who analyzed the character development of Josephine, my biography of Josephine Baker, in order to educate me. Let’s look at these ten elements of character development. And note that it’s not easy to extract character development from plot, nor to cleanly divide each of these ten from the others, but for the sake of simplicity, I’m going to try.

- NAME & AGE

You might not name your character right away, or maybe you’ll rename them a dozen times during the process of writing your fiction. Or maybe you’re writing about a real person. I’m lousy with the hypothetical so in order to make this more concrete, please go along with me, as I use Josephine as a model.

Name: Josephine Baker.

Age is particularly important when writing for children, because one or two or five years makes so much difference in the development of children, in what interests them, how they behave, and what they know about the world. Generally, your character should be the age of your reader or a bit older (kids read up) and your characters should have issues that concern your reader. The age of your main character should be delivered imaginatively (e.g., She showed them just how strong her eight-year-old muscles were. Or: He got his driver’s license the day after his birthday). A biography is different. For instance, Josephine goes from “cradle to grave.”

- GOAL

You’ve heard it before: What does your character want? Sometimes the “goal” can be described as your character’s internal situation or want. Josephine wanted to dance. It was her internal desire. Along the way, maybe she wanted to become famous as well. The goal can change a bit during the course of your story.

- OBSTACLE

Yep, we’ve all heard this: What stands in your character’s way? That obstacle has to be big enough that the reader cares. What would failure mean to your character? The bigger the consequences, the more tension you can create. It’s what keeps your reader turning pages. That usually means tension for our character. This can be described as the external situation. For Josephine, that primary obstacle was racism. And racism is a huge obstacle. No, she didn’t conquer her obstacle, but she worked her whole life to overcome that obstacle (by working for civil rights and by adopting twelve children of different races, ethnicities, and religions to prove they could be brought up together in harmony—to name a couple of Josephine’s struggles against racism).

Yep, we’ve all heard this: What stands in your character’s way? That obstacle has to be big enough that the reader cares. What would failure mean to your character? The bigger the consequences, the more tension you can create. It’s what keeps your reader turning pages. That usually means tension for our character. This can be described as the external situation. For Josephine, that primary obstacle was racism. And racism is a huge obstacle. No, she didn’t conquer her obstacle, but she worked her whole life to overcome that obstacle (by working for civil rights and by adopting twelve children of different races, ethnicities, and religions to prove they could be brought up together in harmony—to name a couple of Josephine’s struggles against racism).

- CHANGE

Why and how does your character change? Your character changes according to what happens—that’s the action or plot of your story. Josephine wanted to dance, but repeatedly hit a wall of racism against black people in the U.S. Why does she change? She has to fight racism and poverty to achieve her goal—to dance. Here’s one of several threads. Josephine grows in self-assurance and gains strength as she risks her life spying for the French and the allies during WWI—all in order to help grant individuals’ freedom. How does she do it? With determination, relentless energy, and imagination—by writing her notes in invisible ink and hiding those notes in her underwear, believing that border patrol would not search a superstar like she was. (She was right).

- CORE STRENGTH

In most stories your main character is your hero, so they must have heroic qualities. Deborah Halverson in her Writing Young Adult Fiction for Dummies (Wiley 2011) calls those qualities “core strength”—those traits that will allow your character to overcome their obstacles. I’d say Josephine’s core strength was her exuberant energy. You can see that overlaps with how she changes.

(Wiley 2011) calls those qualities “core strength”—those traits that will allow your character to overcome their obstacles. I’d say Josephine’s core strength was her exuberant energy. You can see that overlaps with how she changes.

- KEY FLAW

In her book Halverson also discusses the key flaw, or the trait that undermines your character and her core strength. This is essential for creating plot tension. No one is interested in a flawless character. That’s just not real. For Josephine I’d say her key flaw is impulsiveness. Usually the flaw is in opposition to the core strength. Exuberant energy—impulsive energy. Josephine made a lot of mistakes due to her impulsive nature—accompanied by her innocence.

- 7. MOTIVATING BELIEF

Motivating belief is a term coined by the wonderful writer and workshop leader Kathi Appelt. What does your character believe about herself? Once you know this, it will pull your character along through every page of your journey. It directs every step your character takes. Josephine believed she could do anything she set out to do. She was fearless. And this is what makes her a great role model for young readers. We hope that readers will follow Josephine’s example and follow their own dreams—and believe in themselves.

- VOICE

Cheryl Klein, in her book The Magic Words: Writing Great Books for Children and Young Adults (W.W. Norton 2016), defines voice by this equation:

Voice = Point of View (POV) + Tense + Personality

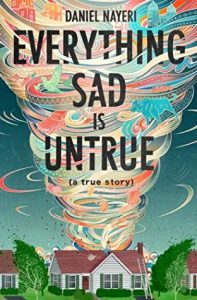

When writing a biography one generally writes in third person POV and past tense. But not always. In fiction, you have more choice. Often you have to experiment to see what combination of POV and tense works for your story. Telling your story in first person, using I and me, can help you get inside the skin of your character. As the writer, you must identify strongly with your character—understand how your character ticks—in order to have that character evoke emotions in your reader. You might want to rewrite a chapter in third person, using he, she, or they. You might even try you—or second person. For example, write to your character, like it’s a letter; or talk directly to your reader as Daniel Nayeri does in Everything Sad is Untrue (Levine Querido 2020). You might try writing your piece in present tense, then change the whole thing to past tense. Keep trying your options until you find the right combination of POV and tense  for your particular story.

for your particular story.

POOF! A funny face.

That used to be fear.

POOF! She’d mock a gesture.

That used to be anger.

Until finally there is a huge explosion of energy and she becomes a star. Josephine’s equation: Third person + past + exuberant, empathetic, compassionate, wild, razzmatazz.

(You can find more about the use of voice or metaphor by reading the former Writer’s Tips https://talesforallages.com/voice-and-first-lines-by-patricia-hruby-powell/

https://talesforallages.com/metaphors-and-similes/

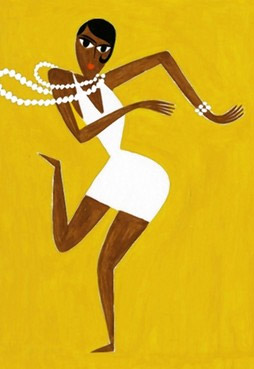

- HOW YOUR CHARACTER MOVES

Does your character take big strides? Or little mincing steps? Do they twitch? Are their heads held high? Are they slumped? By knowing how your character moves, you can employ those details to show them moving through their world. When Josephine dances the Charleston, her

moves, you can employ those details to show them moving through their world. When Josephine dances the Charleston, her

knees squeeze, now fly

heels flap and chop

arms scissor and splay

eyes swivel and pop.

She makes faces. She used her tongue like a scarf. She “stumbled off-balance on elastic legs—on purpose.” She was a clown as well as sexy; she was sexy as well as boyish. She could move like the dickens. All these things make her likeable…which brings us to the final checkpoint.

- EMPATHY (an umbrella category for all the others)

Your character must draw your reader in emotionally. This brings all of the points together. In addition, your character should have a balance of universal and unique traits.

Characters need universal traits so your reader identifies with them. Perhaps your character is fun or funny. Humor can go a long way in connecting character to reader. Perhaps your character is poor, an orphan, or a refugee. People generally sympathize with the underdog. Does your character become powerful? Or selfless? Can your reader identify with your character? That’s what you must ask.

Your character’s unique qualities make them stand out as one of a kind. Maybe they have a remarkable talent. Again, maybe they’re funny, or bold in a charming manner. Or humble. Perhaps your character is a social justice activist and your reader admires that. Many traits are universal, prompting your readers to empathize with your character and their plight, but it’s the details that bring your character into sharp focus. These details are the way you show each character trait in a unique manner.

HOW TO USE THIS INFORMATION

If you get stuck while writing, fill out this chart for main and/or secondary characters. It will give you something to do during those times you just can’t work on your manuscript itself. You will learn about your character and hopefully that will get you back to writing. If you’re a planner, make this chart before you begin to write. Make a quick chart right now of your main characters from a yet-to-be-published manuscript as well as your already published books. See what you discover.

Here are a few to consider. And maybe you see the checkpoints differently than I do. Let me know.

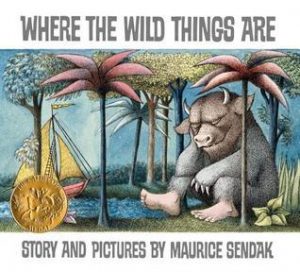

Where the Wild things Are – Maurice Sendak (Harper Collins 1963)

- name/age: Max, about 4

- goal: to get what he wants

- obstacle: parental rules

- change: with imagination, takes a journey and comes back home wanting to be with his parents

- core strength: confidence

- key flaw: naughty

- motivating belief: I am all-powerful.

- voice: Third person + past + playful, wildly imaginative

- move: able to swing in trees, agile

- Empathy: Unique imagination

Universal like every 4-year-old; naughty and loving (& confident)

Last Stop on Market Street by Matt De La Peña, illus. Christian Robinson (Putnam 2015)

1 name/age: CJ, about 4

- goal: To get answers. (He asks why why why?)

- obstacle: traveling through rainy, dirty, broken neighborhood by bus (life’s hardships)

- change: with Nana’s guidance he sees beauty in everything, as she does

- core strength: inquisitive; pretty respectful

- key flaw: a teensy bit rude

- motivating belief: I love my Nana.

- voice: Third person + past + inquisitive, sweet

- move: skips, agile as a child 😉

- Empathy: Unique sweetly inquisitive

Universal sweet but cranky

Elizabeth Acevedo The Poet X (HarperTeen 2018)

- name/age: Xiomara or the Poet X, 15

- goal: freedom; to move through the world unimpeded

- obstacle: sexist misogynist society; her Catholic mami

- change: self-actualizes due to writing and slamming poetry

- strength: strength

- flaw: anger

- motivating belief: I’m not what I’m told I am.

- voice: First person + present + sassy, strong, confident

- move: sexy

- empathy: Unique cares for twin brother, talented poet

Universal rebellious teen

What about your stories?

PATRICIA HRUBY POWELL, who writes in Champaign, Illinois, is comforted by her husband and her Tree Walking Coonhound. And really she’s pretty happy, maybe in part because she feels she’s connecting her adult students and young people to their emotional hearts and helping them build empathy. At least she’s trying to do that. You can reach Patricia at phpowell@talesforallages.com or at talesforallages.com

Leave a Reply