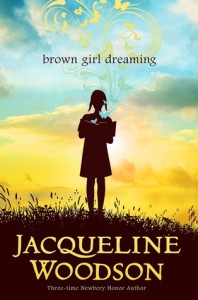

“Brown Girl Dreaming” (Paulsen/Penguin 2014) is Jacqueline Woodson’s memoir about growing up in a loving, but broken family, in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement. Written in accessible vivid verse, and a National Book Award Finalist—we’ll find out tomorrow, November 17, whether it wins. It should.

in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement. Written in accessible vivid verse, and a National Book Award Finalist—we’ll find out tomorrow, November 17, whether it wins. It should.

To set the time frame, the March on Washington took place in August 1963 the year of Woodson’s birth. LBJ signed the Civil Rights Act in 1964. Jacqueline is born in Ohio to a southern mother and a northern father whose grandparents were free men during slave times. The Woodsons were doctors, lawyers, and teachers.

He refuses to visit his wife’s family—the Irbys—in Greenville, SC, saying, “Told her there’s never gonna be a Woodson/ that sits in the back of the bus./ Never gonna be a Woodson that has to/ Yes sir and No sir white people./ Never gonna be a Woodson made to look down/ at the ground.”

So Mama takes her three young children south. Their father shows up, apologizes, but the marriage breaks up soon after. The three children go live with their Irby family in Nicholtown—the black community of segregated Greenville—filled with the scent of pine, honeysuckle and slow days.

Jacqueline is the youngest and not yet one year old. Readers can refer to the Woodson-Irby family tree—their birth and death dates—at the front of the book and handsome family snapshots in the back.

In Nicholtown, Gunnar Irby, Mama’s Daddy, becomes “Daddy” to Jacqueline because that’s what Mama calls him. And he fills the role.

Mama takes off for New York to start a new life. She’ll send for the children as soon as she can. In New York, Jacqueline’s younger brother, Roman, is born.

Jacqueline is not as good a student as her big sister Odella, but she loves words. She knows she wants to write. She adores “Daddy,” her grandfather who sings as he walks the dusty road home from work. After he dies, Grandmother says, “I watch you with your friends and see him all over again.”

Jacqueline Woodson is true to her youthful self and to young reader. She writes, “Sometimes, I don’t know the words for things,/ how to write down the feeling of knowing/ that every dying person leaves something behind.”

The children move to New York, but the grace of the south lives within them. They are urban and country and feel out of place in both places.

As Jacqueline grows up, she refers to song lyrics and MoTown artists. She riffs on Love Train/Soul Train. Her mama loves James Brown. Her Uncle Robert is too wild and pays for it in prison. Jacqueline sees Angela Davis on TV saying “Power to the people.” The Black Panthers are feeding breakfasts to black children out in Los Angeles. You feel the excitement first hand.

I want to quote this whole book so you know its beauty. It’s probably better to buy it or get it from the library.

Patricia Hruby Powell’s book Josephine: The Dazzling Life of Josephine Baker won a Boston Globe Horn Book 2014 Honor for Nonfiction and a Parents Choice Gold Award for Poetry.

Leave a Reply