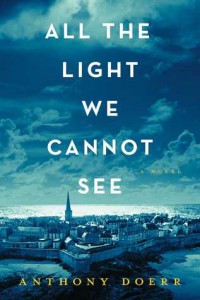

“All the Light We Cannot See” (Scribner 2014) by Anthony Doerr is an adult book, a New York Times Bestseller, and is  literary—meaning it’s thoughtful and beautifully written. It’s a good choice for young adults.

literary—meaning it’s thoughtful and beautifully written. It’s a good choice for young adults.

Marie-Laure lives with her father in Paris as World War II looms. At the opening, she is six years old, has “rapidly deteriorating eyesight” and will soon be blind. The story follows her into young adulthood. Her father, the master of locks at the Museum of Natural History (which is chock full of locks), builds Marie-Laure a model of their neighborhood, which she memorizes by touch so she might navigate the town on her own.

Doerr’s insight into a blind person’s world seems profound.

Werner lives in an orphanage with his sister, Jutta. He becomes obsessed with the workings of radios, becoming, over the years, so adept with the technology that he is sought out by a Nazi military academy. Fellow student, sensitive Frederick, is repeatedly singled out as the weakest cadet and beaten by his schoolmates under the commandant’s approving gaze. Werner would like to help.

“Werner tells himself that he tries. Every night he polishes Frederick’s boots for him until they shine a foot deep—one less reason for . . . an upperclassman to jump on him.” This strikes me as honest—an insufficient thing one can do when you don’t have the power to do the right thing. But it is a too-small comfort to the helper.

Radio-expert Werner, is drafted into Hitler’s army, when he is only sixteen.

When the Germans occupy Paris in 1940, Marie-Laure and her father flee the city to the picturesque walled town of Saint-Malo on the Brittany coast, where they live with Marie’s troubled, but charming great uncle in his mansion. Uncle too has a love of radios and a history of constructing them. But the Germans have confiscated all radios to cut off communication between the Resistance and the allies.

Working as a German soldier, Werner tracks radios being used by Resistance members. His comrades confiscate the radios and shoot their operators. Werner travels through Germany to Russia, back through Germany and to Saint-Malo.

As the stories of the two young people alternate, parallels are drawn. You know that Marie-Laure and Werner’s stories will converge. They will meet. But you don’t know how or when.

Doerr’s writing opens windows through which the reader can see. A minor character is described thus: “Madame seems like a great moving wall of rosebushes, thorny and fragrant and crackling with bees.” There are hundreds of small glowing images, such as: “The typist twists her cigarette into an ashtray, a bright red smear of lipstick on its butt.” Can’t you see it? Even smell it?

I loved this book. I’m pretty sure you won’t be able to stop turning the pages.

Patricia Hruby Powell’s book Josephine: The Dazzling Life of Josephine Baker has recently been awarded a Sibert Honor for Nonfiction as well as a Coretta Scott King Honor for illustration. talesforallages.com

Leave a Reply