We experience the reality of rural nineteenth century Norway in “West of the Moon” (Abrams-Amulet 2014) by Margi Preus, yet we feel immersed in a land of magic. The Norwegians are Christian but are living in a world paralleling  Scandinavian folktales. Superstitions are alive and alluring—with the invisible and wicked huldrefolks lurking near cradles and under bridges.

Scandinavian folktales. Superstitions are alive and alluring—with the invisible and wicked huldrefolks lurking near cradles and under bridges.

It’s not so much what the author says as what she doesn’t say that brings to life this world of awe and magic. This life is so natural to Astri and her little sister Greta, Preus doesn’t tell us about their world—we simply live it alongside of them.

Astri, about fourteen, likens herself to the girl in the folktale who is abducted by a white bear who turns out to be a prince. However, Astri’s abductor, Svaalberd or, as she calls him, goatman, is no prince. As his milkmaid, she milks goats. She says, “Oh, and shovel the snow and chop the wood and haul the wood and clean out the ashes and start the fire and rake the coals and cook the porridge and make the candles and knead the bread. All in the dark, dark, dark.” It’s wintertime.

When the goatman assaults her in her bed, Astri saves herself with the knife she keeps under her pillow. Goatman banishes her to the shed, where she discovers the odd silent Spinning Girl. Astri defends herself again against the entitled goatman. And now the picaresque quality really kicks in and the adventure takes off.

Astri takes Spinning Girl and finds her way back to the farm where she rescues Greta from her greedy aunt. Now they must find a way to get to America where her father has gone to make a better life. And on the road they discover the goatman, Svaalberd dying, probably, from the wounds Astri inflicted on him.

Greta and Astri give him a funeral right on the road. Astri says, “I know Svaalberd was a mean old man, but what made him thus? Did he have that hump as a youngster? That would make for a hard life, wouldn’t it?”

Greta responds, “This is a very strange sermon.” Preus is a master at magic and wisdom and dry wit. And metaphor. Astri says, “The snags in my heart are so tangled and deep, I feel them there, twisted little knots that can’t be undone.”

Astri leaves Spinning Girl at a kind farmer’s home, where she steals a horse. Astri and Greta ride to the sea. One snags a ticket and the other stows away, they both contract cholera and are visited by Death. They meet other Norwegians on their way to America as they make their way.

Preus’ story is inspired by the diary of her great great grandmother, Linka, the young wife of a Lutheran pastor, who met a wild girl all alone crossing from Norway to America in 1850 and asked if she might serve her as a maid.

Patricia Hruby Powell’s new book Josephine: The Dazzling Life of Josephine Baker won a Boston Globe Horn Book 2014 Honor for Nonfiction and a Parents Choice Gold Award for Poetry.

Lockhart, but her actual story begins “summer fifteen” when she is 15. The blueblood Sinclair family own Beechwood Island and all converge there every summer. Her grandparents reign in one mansion and their three middle-aged daughters squabble over the other three island mansions.

Lockhart, but her actual story begins “summer fifteen” when she is 15. The blueblood Sinclair family own Beechwood Island and all converge there every summer. Her grandparents reign in one mansion and their three middle-aged daughters squabble over the other three island mansions. In July 1940 the U.S. and Great Britain were the only democratic powers left in the world. In contrast, U.S. army nurses “enjoyed a casual resort-like atmosphere” in the tropical paradise and fascinating culture of the Philippines. So begins “Pure Grit: How American World War II Nurses Survived Battle and Prison Camp in the Pacific” (Abrams 2014) by Mary Cronk Farrell.

In July 1940 the U.S. and Great Britain were the only democratic powers left in the world. In contrast, U.S. army nurses “enjoyed a casual resort-like atmosphere” in the tropical paradise and fascinating culture of the Philippines. So begins “Pure Grit: How American World War II Nurses Survived Battle and Prison Camp in the Pacific” (Abrams 2014) by Mary Cronk Farrell.

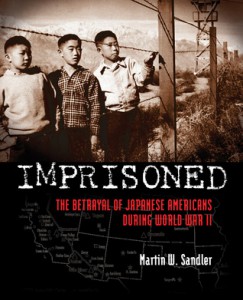

U.S. security. Others said that was ridiculous. The threat-mongers won out and 120,000 loyal Americans of Japanese ancestry were evacuated and detained in remote areas of the U.S. for two years. So we are reminded in “Imprisoned: The Betrayal of Japanese Americans During World War II” by Martin W. Sandler (Walker 2013).

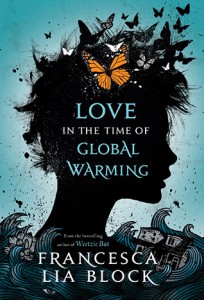

U.S. security. Others said that was ridiculous. The threat-mongers won out and 120,000 loyal Americans of Japanese ancestry were evacuated and detained in remote areas of the U.S. for two years. So we are reminded in “Imprisoned: The Betrayal of Japanese Americans During World War II” by Martin W. Sandler (Walker 2013). last person left on earth searching through stopped cars for survivors. But Francesca Lia Block’s devastated post-apocalypse world is oddly beautiful in “Love in the Time of Global Warming” (Christy Ottiaviano/Holt 2013). I couldn’t stop turning the pages.

last person left on earth searching through stopped cars for survivors. But Francesca Lia Block’s devastated post-apocalypse world is oddly beautiful in “Love in the Time of Global Warming” (Christy Ottiaviano/Holt 2013). I couldn’t stop turning the pages.