Graphic novels, so often bigger than life, can sometimes be exactly like life. Cousins Jillian Tamaki (illustrator) and Mariko Tamaki (writer) raise the bar of authenticity in “This One Summer” (First Second 2014) a coming-of-age story. Preteens Rose and Windy meet at their summer cottages every summer, but this time it’s different.

Tamaki (illustrator) and Mariko Tamaki (writer) raise the bar of authenticity in “This One Summer” (First Second 2014) a coming-of-age story. Preteens Rose and Windy meet at their summer cottages every summer, but this time it’s different.

Rather than simply playing in the water and digging holes in the sand, they are attracted to an older group centered at the convenience store where they rent R-rated thrillers and eavesdrop on older teens and their problems. Rose develops a crush on the boy whose girl friend is probably pregnant. At home Rose’s parents are fighting.

Rose, a year older than Windy, offers a juxtaposition and a view of changing attitudes of human development. The girls obsess over words like “slut” the meaning of blow jobs and the wonderment of “boobs” in the course of their easy slow summer life. They experience the very real meanness of those slightly older girls. But they experience these things differently—one from the other. Chubby Windy is often wired on sugar while Rose appears calm and sometimes sullen.

Jillian’s paintings, all a deep blue-purple are often lush, such as scenes showing the dappled light filtered through trees onto the gravel road leading to the lake. Or when she depict emotions through unexaggerated but telling postures or facial expressions. The way Jillian shows Rose’s unhappy mother who appears haggard in her depression, a few years back in flashback, is just-right in her prettiness.

The story that Mariko’s tells is true to life. Rose’s parents’ fighting is a real parental fight. When the girls fight, it is just as these girls might. Rose calls the pregnant girl a slut. Windy questions the assessment and Windy walks away to dig a hole in the sand as they did when they were little. Rose returns eventually and joins her. Kids grow up at different rates, but they can remain friends.

Relatives arrive at the lake. You know these people, whether they are like your own family or someone else’s. They’re real.

One of my favorite scenes is the girls discussing the older teens while shampooing their hair in the lake. What nostalgia! What a sensuous scene! Another is the nighttime bonfire which sets the climax of the story is a study in light. And the right climax for this story—not original, perhaps—but it loosely ties up the various threads, not too tight, not too tidily, but in a way that is true to life and still satisfying to the reader.

If you’re not a reader of graphic novels, you might want to try again with “This One Summer.”

Patricia Hruby Powell’s book Josephine: The Dazzling Life of Josephine Baker was chosen by the Huffington Post as the Best Picture Book Biography (artist) and is on various Best Books of the 2014, including, PBS, NPR, NYPL. talesforallages.com

reminded of my sister describing her snowboarding son as “tragically cool” from the time he was in 4th grade. She was speaking of his attitude and it always made me laugh. But saying that the teenage artist phenomenon, Addison Stone, was “tragically hip” is, indeed, a tragedy.

reminded of my sister describing her snowboarding son as “tragically cool” from the time he was in 4th grade. She was speaking of his attitude and it always made me laugh. But saying that the teenage artist phenomenon, Addison Stone, was “tragically hip” is, indeed, a tragedy. adult novel “I’ll Give You the Sun” (Dial 2014), as she did in her first book “The Sky is Everywhere.”

adult novel “I’ll Give You the Sun” (Dial 2014), as she did in her first book “The Sky is Everywhere.” beach. Noah snaps photos of them, then destroys them before the tides wash them away. Then he deletes the pictures so his mother doesn’t see them. Afterall, he finally has his mother’s undivided attention. Noah feels that he has finally eclipsed Jude, the golden girl, in his mother’s eyes.

beach. Noah snaps photos of them, then destroys them before the tides wash them away. Then he deletes the pictures so his mother doesn’t see them. Afterall, he finally has his mother’s undivided attention. Noah feels that he has finally eclipsed Jude, the golden girl, in his mother’s eyes. in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement. Written in accessible vivid verse, and a National Book Award Finalist—we’ll find out tomorrow, November 17, whether it wins. It should.

in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement. Written in accessible vivid verse, and a National Book Award Finalist—we’ll find out tomorrow, November 17, whether it wins. It should. departments.

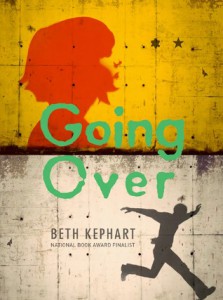

departments. Berlin (a federal republic) and did not come down until 1989. For those 28 years the Wall and its towers and armed guards prevented the mass defection from the communist East Bloc to the free west during the cold war. Families, friends, and lovers were split apart.

Berlin (a federal republic) and did not come down until 1989. For those 28 years the Wall and its towers and armed guards prevented the mass defection from the communist East Bloc to the free west during the cold war. Families, friends, and lovers were split apart. A subplot involving Ada’s favorite Turkish pre-schooler, Savas, and his abused mother brings out an aspect of the story of Berlin of which I knew nothing. In fact I’ve read no other fiction involving this dramatic historic era and place. The relationship of the grandmothers gives us a view of young adults in war time Berlin, countering the punk history of the two protagonists.

A subplot involving Ada’s favorite Turkish pre-schooler, Savas, and his abused mother brings out an aspect of the story of Berlin of which I knew nothing. In fact I’ve read no other fiction involving this dramatic historic era and place. The relationship of the grandmothers gives us a view of young adults in war time Berlin, countering the punk history of the two protagonists.