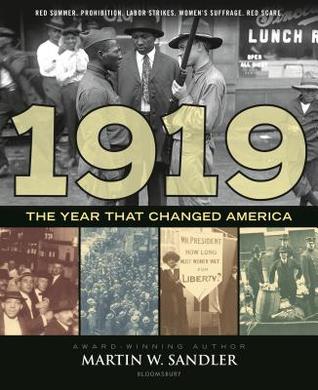

Nine boys (from nine to fifteen years old) and three men are dropped off at the nearly vertical Warrior Stac—one of the tiny rock islands of the St. Kilda Archipelago in the far northwest of Scotland. The year is 1727. Every summer a group of boys goes “fowling” to collect gannets, puffins, petrels and other birds for the meat, eggs, feathers, bones and oil to pay as rent to the owner of their island, Hirta. The amazing Geraldine McCaughrean spins her tale from a true event in “Where the World Ends” (Flat Iron 2017).

Archipelago in the far northwest of Scotland. The year is 1727. Every summer a group of boys goes “fowling” to collect gannets, puffins, petrels and other birds for the meat, eggs, feathers, bones and oil to pay as rent to the owner of their island, Hirta. The amazing Geraldine McCaughrean spins her tale from a true event in “Where the World Ends” (Flat Iron 2017).

After a couple months the Hirta boat will fetch the men and boys home, with their haul of dead birds. But the boat doesn’t arrive. Day after day they wait.

Wise and humble Quill, one of the older boys, has become a natural leader. He comforts the younger boys with stories—although Quill doesn’t understand why they look up to him. He also fantasizes about the young woman, Murdina, who had visited Hirta last year from the mainland.

One of the men, who insists upon being called Colonel Cane, the grave digger in their small community on Hirta, names himself the Minister of the boys. He tells the boys the world has ended and their people have been taken by angels to Heaven and forgotten those on Warrior Stac. Of course the boys are distraught. Cane then requires the boys to confess to him. Jealous of Quill’s power, Cane banishes Quill.

As Quill climbs down the treacherous cliff from Midway Bothy to Lower Bothy, rage keeps Quill alive although he is “drowning in dark.” He finds a shallow cave to protect him from cold and stormy weather. The youngest boy, Davie, is the first to visit Quill.

One by one the other boys visit him in his exile and Quill comforts them by giving each a job according to how they are needed: “Keeper of Faces,” “Keeper of Memories.” He advises them “Do not dwell on the unbearable.”

Kenneth is the teen bully who was “the great snitcher, who used information like a crowbar to thrash his way through the world.” Even he visits Quill as does Quill’s best friend Murdo. But Murdo grows jealous of Quill. The reader will wonder is this a redux of Lord of the Flies?

This richly imagined world, to me, offers more, partly by imparting the technology such as ropes used to help scale escarpments—made on Hirta of sheep skin and horsehair. While exhiled on the stac, the boys string a horsehair taken from a rope through an oily bird, for a wick and it becomes a candle.

In time the boys give up hope, the birds leave for the winter, the storms arrive in full force—and the months pass. Starvation sets in.

Spoiler: The world had not ended, but a smallpox epidemic reduced their Hirta community to a handful of people and no one was able to captain the boat to Warrior Stac. In actual history, every man and boy returned home and found only one Hirta survivor. Both stories are riveting.

Patricia Hruby Powell’s Lift As You Climb: The Story of Ella Baker will be celebrated at her Virtual Book Release Party. Check https://talesforallages.com/ for link.