WRITING TIPS

RESEARCHING FOR FICTION AND NONFICTION

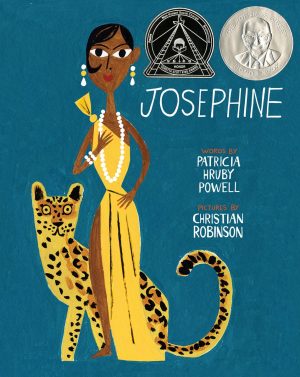

by Patricia Hruby Powell

Whether we write fiction or nonfiction, we need to research. It’s a bit more challenging nowadays, with many of us sheltering at home, but it’s still completely doable.

What if there’s a scene in your story involving a goat? You don’t know any goats? Ask on Facebook who has goats. Visiting goats is an outdoor activity that you could do, whatever sheltering you’re practicing.

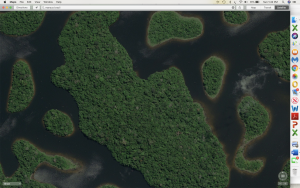

What if you’re writing about a boy who finds the entrance to the Amazon Rainforest in his attic? You must research the rainforest and its peoples and how to find nuts filled with nutritious squirming larvae. If that boy lives in New Bedford, Massachusetts, because your plot requires a place important to the historic whaling industry, look online for a New Bedford museum. Contact the museum. Speak to an expert. (More on experts to come).

If you can’t visit the Amazon, Google Earth the city of Manaus, Brazil, and work outward from there.

Those suggestions cover my unpublished novel—WAITING FOR RAIN. (I have two unpublished novels. But I didn’t give up. I kept writing and improving my skills until I found a niche in narrative nonfiction, and now I’m expanding upon that niche).

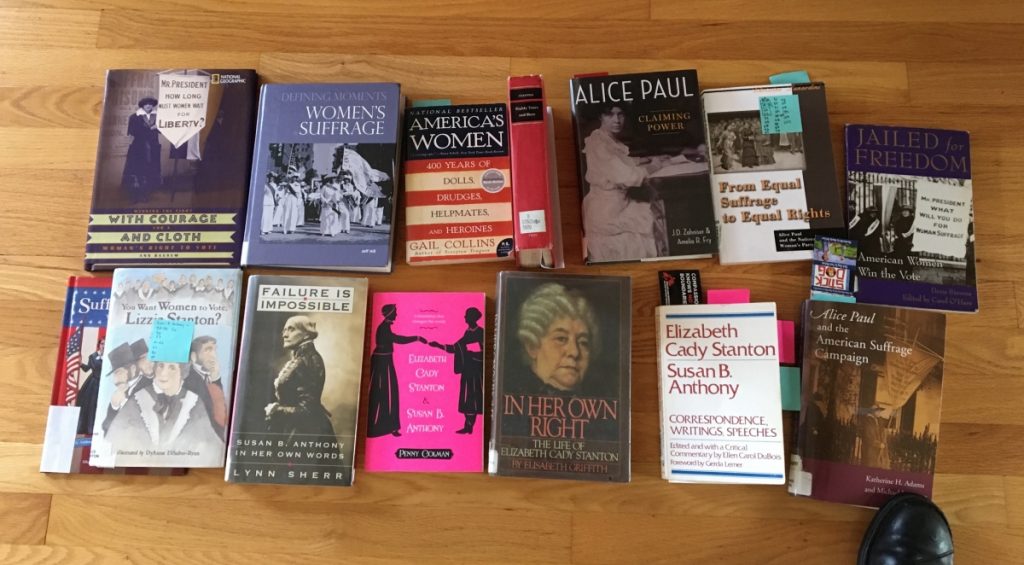

Books and Libraries

Begin your research on the internet. Print articles about your subject, including the bibliographies. Maybe a detail in an article will guide you to the slant you’ll want to take on a nonfiction project. Or you might realize the plot you’ll use for a novel, picture book, or graphic novel.

Using the listings in your bibliographies, search your local libraries via computer; also use keywords or subject headings. For me, “libraries” include not only the fabulous public library system in my town of Champaign but all other Illinois Libraries as well, which anyone can access at https://www.library.illinois.edu/search-tools/. Every Illinois citizen is entitled to a library card for checking books out from this extensive system. Alternatively, your public library can connect you to Worldshare: Libraries Worldwide for specific harder-to-obtain resources. Once you might have collected a mountain of books from your library yourself. Now you can request books and pick them up curbside or from a “hold shelf.”

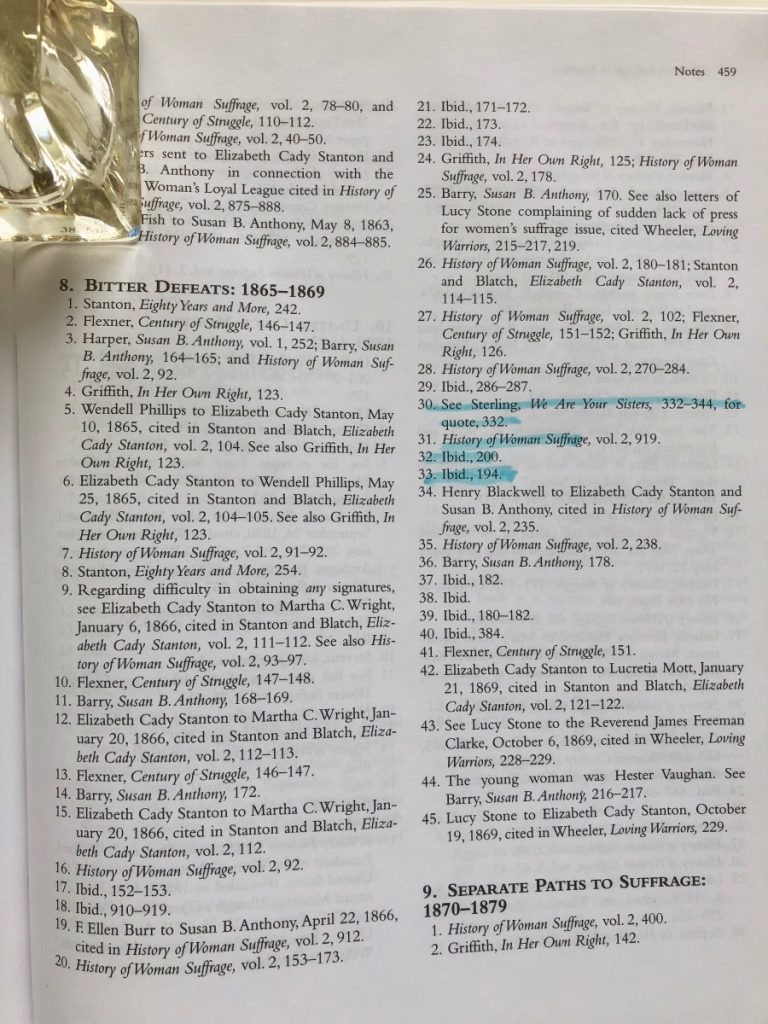

Read those books. If you come across necessary, obscure, or fascinating facts and they’re marked by a superscripted number, refer to those numbers in the footnotes, “Notes,” or “Endnotes,” which will give a source. And if that fabulous fact was not marked by a superscripted number, fear not. You can do a little Sherlock Holmes work in the Notes section. Is there a quote in the text that’s abbreviated in the Notes and given a source? Work forward or back from that endnote and speculate on the source for your fabulous fact.

endnote and speculate on the source for your fabulous fact.

Notes at the back of the book are probably divided by chapter, which in turn will direct you to the source used by the author and found in the bibliography, if there is one. That source might well be a primary source. If the source is secondary, get whatever book or item that source may reference, and see if it holds a citation to the primary source. It’s good to use both primary and secondary sources.

Primary and Secondary Sources

Primary source – a document, first-hand account, or other source that constitutes direct evidence of an object of study.[i] “Direct” is the keyword here. This might be an “account” or quote or description by your subject; it might be a newspaper article or letter about your subject, contemporary to when it happened. Such sources are “first public accounts,” which also include autobiographies, diaries, interviews, oral histories, birth and death certificates, photos, and artifacts such as clothing or furniture, to name a few. These intellectual and emotional “properties” bring you close to your subject. Visiting Emily Dickinson’s home in Amherst, Massachusetts, I saw her white dress. What an emotional zinger! She wore it. I felt  almost as if I were facing the reclusive poet herself.

almost as if I were facing the reclusive poet herself.

Secondary sources – a book, article, or other source that provides information about an object of study but does not constitute direct, first-hand evidence.[ii] Authors of secondary sources have interpreted, discussed, or analyzed primary sources. Newspaper and magazine articles after the event, biographies, history books, and dictionaries are secondary sources. And they are valuable.

Both primary and secondary sources could be factual or not. So you must read a whole lot on your subject to be able to discern the “truth.”

Internet

Just as readers must evaluate books they must also evaluate internet sources. Here are a few dependable sites and internet “avenues.”

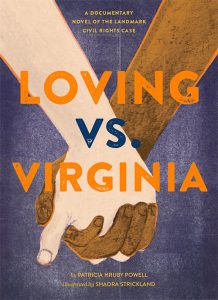

The Library of Congress owns “collections”—archival materials including photos, theater programs, letters, and much more. When researching Loving vs. Virginia I depended on this extensive site for finding photos to be published in that book. For my upcoming book about Martha Graham I used the Martha Graham collection for primary sources—in particular, concert program notes, which spoke of Martha’s performance intentions, costuming, and lighting as well as critical reviews contemporary to her performances.

The New York Public Library also has “collections.” The Martha Graham Dance Company has just given a load of its archival material to the NYPL, including Martha’s letters to composers, “outlines” of dances, old films of her early works, and much more. The bad news: It will take years for the library to digitize these materials, and traveling during the era of Covid-19 is problematic. The good news: Covid-19 has brought a million Zoom experiences, thus providing new paths to research.

Due to the pandemic, the Graham Company is Zooming premieres of Martha’s past dances, which are accompanied by live and recorded “chats.” I started asking small polite questions during those chats and increased my presence little by little. I’ve now contacted the present director of the Graham Company. We’ve scheduled an extensive conversation together. Like that director, other experts also chat and I’m developing relationships with them. I mention this here to say, follow leads. Use your imagination to get to leads. I fancy I’m a latter-day Sherlock Holmes. Research is fun.

University and museum archives, often available online, contain interviews with all kinds of people. Interviews with your subject are important primary sources. (How to conduct the personal interview requires its own article).

The online thesaurus is invaluable. Dig deeply—the words you choose must be carefully analyzed, considered. Also, by linking from one possible word to another (online) you might find a new way to describe what you were initially looking for. This is good.

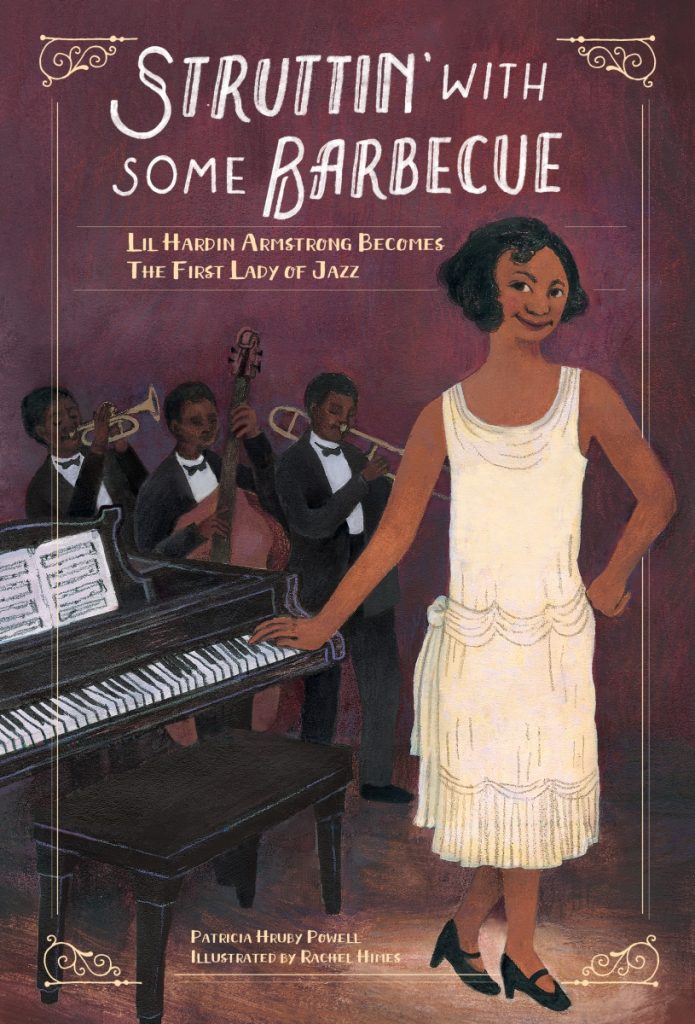

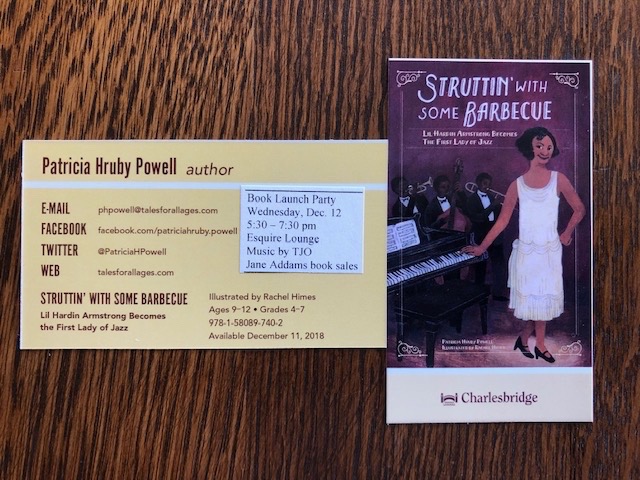

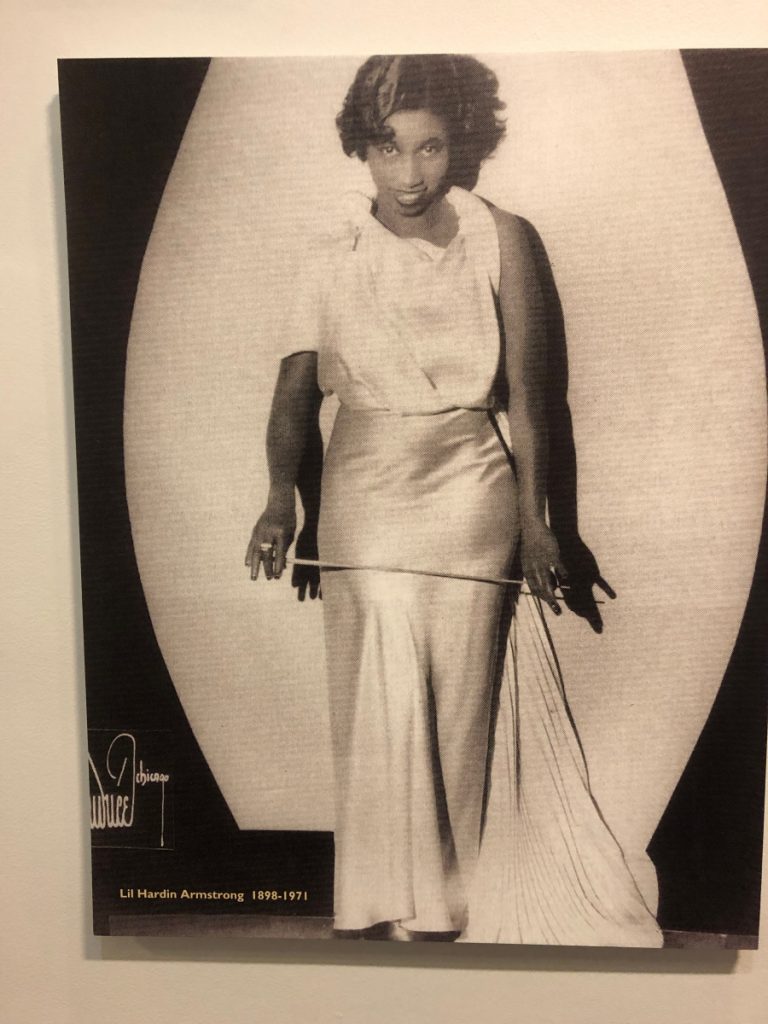

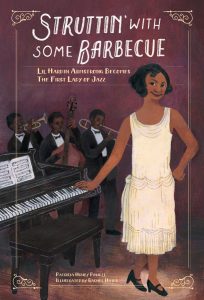

Slang dictionaries are useful, particularly for historic fiction and nonfiction. Again, if you find a word once, keep looking. You want it to be authentic. Not everything you find is accurate. Use books written contemporary to the time and within the universe of your subject. While writing Struttin’ With Some Barbecue: Lil Hardin Armstrong Becomes the First Lady of Jazz (Charlesbridge 2018) I found the memoir Really the Blues (Random House 1946) by jazz player Mezz Mezzrow. Mezz and Lil were contemporaries, both working as jazz musicians. Mezz loved slang so much he included an outrageous glossary of slang in his book. And because I know jazz musicians, I know that they are big-time slang users. But you must be sure that any particular phrase was used during the era in which you’re writing.

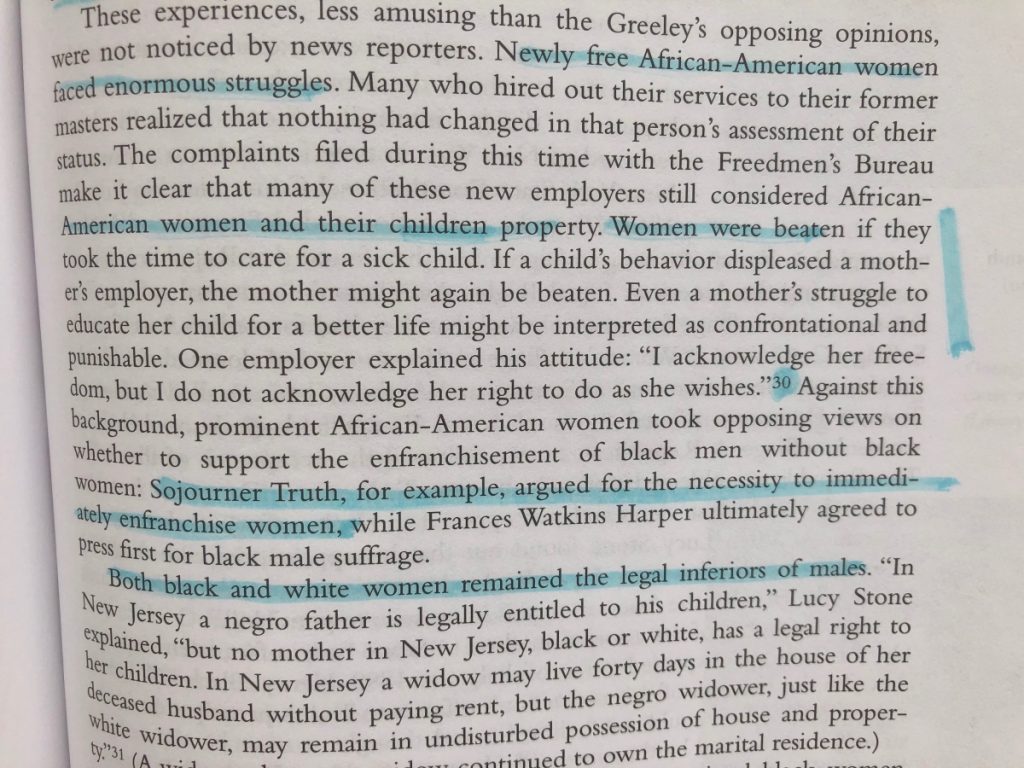

Wikipedia, although useful, has its drawbacks, mainly having to do with “authority.” Anyone can write and/or edit a Wikipedia article. Still, I print those general articles (and file them under “Articles”) to refer to later. By the time I’m writing, because I’ve read so extensively, I’m pretty certain of overall facts about my subject. If there are discrepancies—and there always are—keep reading and try to ascertain what is accurate. Flag inaccuracies. The point being that it’s important to find several references for any fact you want to use.

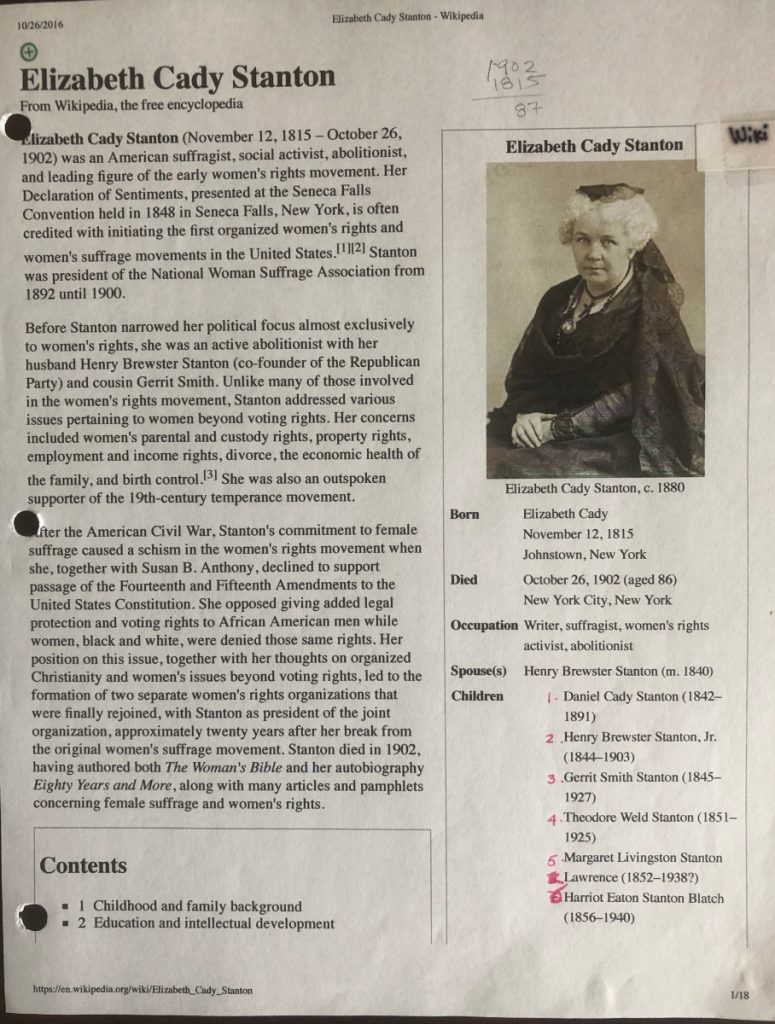

Wikipedia might be the first article you read about a subject. You’ve printed it and highlighted potentially useful sources from its footnotes. Consider the Wikipedia article about Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who is one of nine “characters” in my (as yet unnamed) Women’s Suffrage Project. As I write about Stanton’s relationship with Susan B. Anthony through the years, I can check that Wikipedia article for the years of her children’s births, which are listed on the first page. I can show Susan B. Anthony visiting Elizabeth and caring for the “correct” baby. Which boys were outside playing?

Wikipedia article about Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who is one of nine “characters” in my (as yet unnamed) Women’s Suffrage Project. As I write about Stanton’s relationship with Susan B. Anthony through the years, I can check that Wikipedia article for the years of her children’s births, which are listed on the first page. I can show Susan B. Anthony visiting Elizabeth and caring for the “correct” baby. Which boys were outside playing?

Historic weather reports can offer pithy details. For Loving vs. Virginia, I looked up the Richmond County, Virginia, weather for July 10, 1958—where and when Richard and Mildred Loving, a white man and a black woman, were sleeping five weeks after they married. The hot humid night helped set the tension for the scene. The police, without knocking, entered their house and arrested them.

Google Earth, as I mentioned before, can help you visit a place. Look around. If your setting is historic you’ll have to depend on photos, newspapers, historic newsreels. Searching is not always easy, but if you take your time, it’s fun. Go from site to site. Who knows what pithy detail will arise?

Photos

You should take photos throughout the research process. I use my phone to snap bibliographies, documents, museum artifacts. Collect your photos in files on your computer. You’re never sure what you’ll need. If you’re writing an illustrated book, it could be helpful to pass these photos to your editor who can pass them to your illustrator. They’ll be grateful.

As with conducting interviews, how to properly collect photos for a book to be published requires an article of its own. But start with the Library of Congress database. You’ll need to find out if the photos you want to use are in the public domain. If not, who owns them? The creator? What will they charge you?

Experts

To find experts, start your search with the internet. Then follow where it leads you. Experts can be found at museums, historical societies, science institutions—all over the place. Use website “contact” links. Email or telephone your expert. While researching Loving vs. Virginia, I phoned the curator of the Tappahannock Historical Society, which was near my subjects’ home in Central Point, Virginia. I wanted details about the “whites only” section of the local movie theater in order to write a scene about Richard and Mildred on a date. The curator not only described the urine-smelling stairway to the black section, but why that was. It “made” my scene. He directed me to Cleopatra Coleman, an expert on the one-room schoolhouses of the day that were supported by the Virginia Baptist churches in the area where the Lovings lived. One expert leads you to the next. You get the idea.

Another way to find experts is to read acknowledgements in the back of books to see who is being thanked for what—experts supply an abundance of information and there’s an abundance of experts on limitless topics.

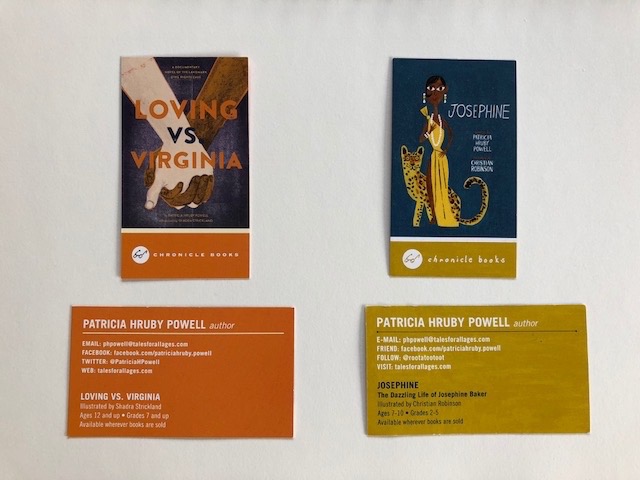

Which doesn’t mean that experts are always correct. My expert reader for Josephine informed my publisher that Josephine was born in East St. Louis, Illinois, rather than St. Louis, Missouri. I felt confident that she was born in St. Louis, so I endeavored to obtain Josephine’s birth certificate. I contacted the county courthouse in St. Louis, which can usually be done via email. I paid the required small fee. Well, darn, I received a letter saying that the records for those particular years of St. Louis births had all been destroyed in a fire. Sherlock Homes doesn’t give up. Josephine’s thirteenth “adopted” child and her one-time manager, wrote a biography of Josephine describing the hospital in which Josephine was born, the address she and her mother went home to, her grandmother’s address, her aunt’s address—all in St. Louis. That thirteenth child was a family member. I trusted him with this information.

Which reminds me to say, keep constant track of your references. I learned the hard way and had to re-re-research Josephine. Some people use Scrivener or Evernote to maintain their sources. Being an old-fashioned girl, I include mine in my manuscript Endnotes, a feature of Microsoft Word.

Finally, if you’re writing outside your culture, you’ll need to do more exhaustive research. You’ll need an expert reader at the least and, as the times change, you might need a collaborator.

End Benefits

I personally love research. I often start writing and continue to research as I realize I need more information. Or perhaps a new collection has just been released to the New York Public Library. You will find pithy details that will wake up and deepen your writing. Almost certainly, you’ll find your next subject.

Patricia Hruby Powell, who writes in Champaign, Illinois, is comforted by her husband and her Tree Walking Coonhound. And really she’s pretty happy, maybe in part because she feels she’s connecting young people to their emotional hearts and helping them build empathy. At least she’s trying to do that. You can reach Patricia at phpowell@talesforallages.com or at talesforallages.com

[i] https://tinyurl.com/y6vtrm2b

[ii] https://preview.tinyurl.com/y86hq3dn

Fox the Tiger (Balzer & Bray 2018) by Corey R. Tabor, an award winning first reader, begins:

Fox the Tiger (Balzer & Bray 2018) by Corey R. Tabor, an award winning first reader, begins:

In the same way that we bring our experience to writing, we bring our experience to launching a book. I hope to give you some ideas that might help you launch your baby. The book, of course, helps dictate the party theme. Holiday books are great party inspirers. I know what I’d do if I had a tea party depicted in a book. Dog or cat washing? I’d throw a wet and messy bash. If I happened to have a book about a construction site, I’d throw a site-specific event. We have a massive square mile construction site a couple miles west of town. My hound loves it. Boy children would go nuts. Some girls, too.

In the same way that we bring our experience to writing, we bring our experience to launching a book. I hope to give you some ideas that might help you launch your baby. The book, of course, helps dictate the party theme. Holiday books are great party inspirers. I know what I’d do if I had a tea party depicted in a book. Dog or cat washing? I’d throw a wet and messy bash. If I happened to have a book about a construction site, I’d throw a site-specific event. We have a massive square mile construction site a couple miles west of town. My hound loves it. Boy children would go nuts. Some girls, too.