Finn O’Sullivan lives in Bone Gap, Illinois with his older brother Sean, at the edge of town  among the cornstalks, in the young adult book “Bone Gap” (Balzer & Bray 2015) by Laura Ruby. Finn is called Moonface, Sidetrack, and Spaceman by his friends—in fact by the whole town.

among the cornstalks, in the young adult book “Bone Gap” (Balzer & Bray 2015) by Laura Ruby. Finn is called Moonface, Sidetrack, and Spaceman by his friends—in fact by the whole town.

Sean is a paramedic who has put off medical school until Finn finishes high school since their mother has run off to Oregon with a dentist. A young woman, Roza, shows up dirty and bruised, in their barn. As she recovers she cooks Polish food, gardens, and the boys begin to recover from the hurt of their missing mother.

But then Roza goes missing. Finn witnesses the man in the black SUV carry her off while the two are at the fair together, but he can’t describe the abductor except to say he moved like a “cornstalk in the wind.” The police detective is disgruntled by Finn’s inability to describe the man. Both the detective and Sean who has fallen in love with the beautiful Roza, blame Finn for letting Roza be taken.

All is real, if creepy, until a black Arabian horse arrives in the barn from nowhere—and things get strange. Or magical. Finn rides the horse to Petey’s, who everyone thinks is an ugly girl, except Finn. Finn and Petey ride the horse and leap through the air and sail for what feels like forever. This magic happens without a hitch—smoothly, believably.

Roza’s garden wilts and dies. And then you get it. It has something to do with Greek mythology. Roza is Demeter? Whose daughter Persephone has been taken to the underworld. Or is Roza Persephone? Abducted to the underworld? Demeter might be Roza’s grandmother back in Poland.

Ruby writes chapters from Roza’s viewpoint as well as Finn’s. The man who took her is mysterious and cruel and clearly he is the Hades character.

Can someone pass from Finn’s world to the underworld somewhere in the endless cornfields surrounding their house? If so, how do you find the way in? Bone Gap is indeed the name of a small town in southern Illinois, but does it also suggest a passage to the underworld? Why can’t Finn describe the man who took Roza?

To say more would give away the reason you should read this book.

I was lost in the pages of this remarkable story of magical realism, largely because there is so much realism. Laura Ruby writes fantasy books for middle school readers and realistic high school stories for young adults. She has brought these genres—fantasy and realism—together in a tour de force.

Patricia Hruby Powell’s book Josephine: The Dazzling Life of Josephine Baker has recently been awarded a Sibert Honor for Nonfiction as well as a Coretta Scott King Honor for illustration. talesforallages.com

and Death” (Arthur Levine 2015), Love is personified as a gentle man. And Death, a hard woman.

and Death” (Arthur Levine 2015), Love is personified as a gentle man. And Death, a hard woman. particular, by young adult women. There are so many points to ponder and discuss.

particular, by young adult women. There are so many points to ponder and discuss. air force career in “How I Discovered Poetry” (Dial 2014).

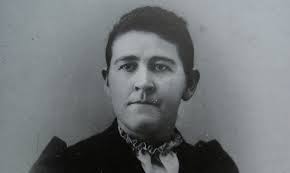

air force career in “How I Discovered Poetry” (Dial 2014). story of Lucy Lobdell who became Mrs. George Slater and bore Helen Slater before becoming Joseph Lobdell in 1853. The author began his project as non-fiction about this historic figure before changing to the fictionalized “memoir” it has become. Although written for an adult readership, it’s a good match for young adults who are perhaps the first generation to consider transgender people as quite normal.

story of Lucy Lobdell who became Mrs. George Slater and bore Helen Slater before becoming Joseph Lobdell in 1853. The author began his project as non-fiction about this historic figure before changing to the fictionalized “memoir” it has become. Although written for an adult readership, it’s a good match for young adults who are perhaps the first generation to consider transgender people as quite normal.

American city. A broad cast of characters each reports the incident differently, in Kekla Magoon’s “How It Went Down” (Holt 2014).

American city. A broad cast of characters each reports the incident differently, in Kekla Magoon’s “How It Went Down” (Holt 2014).