What do you know about Nijinsky? He was a legendary dancer, homosexual, he caused a riot in Paris when he performed to Stravinsky’s music? All true, but there is so much more as shown in Lynn Curlee’s “The Great Nijinsky: God of Dance” (Charlesbridge 2019).

but there is so much more as shown in Lynn Curlee’s “The Great Nijinsky: God of Dance” (Charlesbridge 2019).

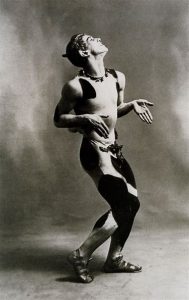

The photos in the book show a stocky, plain, stationary Slavic-looking man with decidedly small feet. Only one photo hints at Nijinsky’s brilliance as a dancer. Yet the artwork of the author/illustrator suggests the dancer’s theatrical genius.

Born in 1890, a Pole in Russia, he was educated at the preeminent Imperial Ballet School in St. Petersburg and joined the Imperial Ballet upon graduation. In 1909, he was wooed by the great impresario Sergei Diaghilev to dance in his Ballet Russe. At the time, Vaslav Nijinsky was heterosexual but Diaghilev required complete dedication which included being his lover. With Nijinsky dancing and luminaries Michel Fokine as choreographer and artist Leon Bakst producing sets and costumes, Ballet Russe was innovative beyond anything Paris or the world had ever seen.

The book is divided by the great ballets, each with an illustration, program details, blurbs from reviews, and the ballet’s story. They include Fokine’s Firebird, Scheherazade, Carnaval, Specter of the Rose, Petrushka—all titles known to balletomanes. The story of Nijinsky’s life is interspersed. Nijinsky soon came to hate Diaghilev, but Diaghilev was conducting Nijinsky’s remarkable career, so the dancer remained living with the entrepreneur.

Whereas Nijinsky was thought to be a dull, shy man, he was lauded as a miracle on stage—the most accomplished, brilliant dancer of the early 20th century. This is entirely based on memories, reviews, photos, because there is absolutely no existing footage of Nijinsky’s dancing. He was known as a sex symbol—a genius performer.

In 1912 Nijinsky choreographed Afternoon of a Faun on the Ballet Russe, to music of Debussy. A remarkable costume sketch by Leon Bakst is included and the dance is described as, “spare, severe, strangely erotic, totally original, and very beautiful.” Nijinsky required his dancers to abandon their classical training to execute challenging movement created to get from one “awkward” pose to the next. Some audience members, accustomed to lyrical Russian ballet hated it; some loved it. Regardless, Nijinsky was considered the “God of Dance.”

In 1912 Nijinsky choreographed Afternoon of a Faun on the Ballet Russe, to music of Debussy. A remarkable costume sketch by Leon Bakst is included and the dance is described as, “spare, severe, strangely erotic, totally original, and very beautiful.” Nijinsky required his dancers to abandon their classical training to execute challenging movement created to get from one “awkward” pose to the next. Some audience members, accustomed to lyrical Russian ballet hated it; some loved it. Regardless, Nijinsky was considered the “God of Dance.”

For the 1913 premier of Nijinsky’s Rite of Spring, Igor Stravinsky “composed a revolutionary score so audacious and original, so brutal and harsh, that when combined with Nijinsky’s unconventional choreography, it caused the audience to riot.” The yelling Parisians drowned out the orchestra so the dancers couldn’t hear it. Fist fights broke out amongst the  audience.

audience.

Soon after, the Ballet Russe was booked to tour South America. Diaghilev stayed behind. On the voyage Nijinsky met a beautiful Budapest society girl, Romola de Pulszky, and married her, never thinking that Diaghilev would withdraw his support. But he did. Nijinsky’s career and mental health plummeted. Without the support of Diaghilev, Nijinsky, unable to dance, spiraled into mental illness and was institutionalized in 1919. He died in an asylum in 1950.

His life was tragic, his legacy stellar. I, among so many other dancers and admirers long to have seen this man dance.

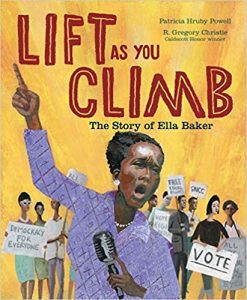

Patricia Hruby Powell’s newest book, Lift As You Climb: The Story of Ella Baker is available, signed from Jane Addams Bookstore or available wherever you buy books. talesforallages.com