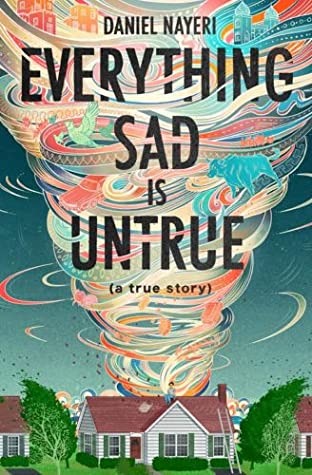

“Everything Sad is Untrue” (Levine Querido 2020) is Daniel Nayeri’s childhood story of fleeing Iran with his mother and sister. By a series of minor  miracles the little family manages to evade Iran’s secret police and get to Italy where they stop at a refugee camp for a couple of years before landing in Oklahoma. Born as Khosrou, he is now Daniel.

miracles the little family manages to evade Iran’s secret police and get to Italy where they stop at a refugee camp for a couple of years before landing in Oklahoma. Born as Khosrou, he is now Daniel.

As the book cover suggests, the story swirls in time like an Oklahoma cyclone with bits of Persian artifacts caught in the swirl. Starting at eight-years-old, he stands before his American classmates and tells wild stories that are structured like a French braid. Choose your metaphor.

He takes strands from the rich Persian culture of myths, pulls in strands of his ancestors who he knows through stories, all vividly pulled from his own immigrant child life. You hear about evil uncles who betrayed his grandmother—another strong Persian woman who had to flee Iran. Speaking of those uncles, Nayeri dispenses universal wisdom, such as, “One is the kind of villain who wants more for himself. The other is the kind who wants less for others.” He admits that he doesn’t have all the details so details of his story are speculated. He walks us through the steps of how he chooses those speculated details, and along the way teaches us how to write.

Scheherazade wove stories to entertain the king to keep herself alive. Daniel tells stories in an attempt to enter a new culture and be known for who he is. “I am ugly and I speak funny. I am poor. My clothes are used and my food smells bad. I pick my nose. I don’t know the jokes and stories you like, or the rules to the games. I don’t know what anybody wants from me…Like you, I want a friend.” See how gracefully he invokes “you,” the second person point of view? And we feel completely involved in his world including the tarofing—where you compete with your neighbors in lies so polite you can’t find the truth. This is Persian etiquette. Nayeri shows so much—such as the cruelty of other children who dismiss him, but never does it feel like he’s whining. On the contrary, he’s insisting on being known.

Food plays a big part. “Soon the dinner carpet was full with trays of kebab, grilled onions and tomatoes, platters of fresh chives, green and purple basil, cilantro, radishes and dill…A stew of chickpea, lamb, crispy shallots and fried mint was the khan’s favorite.”

As he advances to middle school and loving Kelly, he says, “I don’t want to stop just because she laughs at me. I want to stay in love with her until she realizes I am a person.”

This books is like no other. This new publisher Levine Querido is like no other. Check both of them out. Please.

Patricia Hruby Powell is the author of the award-winning Josephine; Loving vs Virginia; and Struttin’ With Some Barbecue and the new Lift As You Climb. She teaches community classes in writing at Parkland College. talesforallages.com