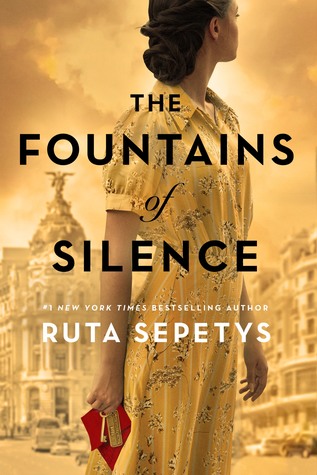

Daniel Matheson, 18 years old, visits Madrid with his oil baron father and Spanish born mother in 1957.  Generalissimo Franco, the fascist dictator, has been in power since 1936 and will continue to rule until his death in 1975. Ruta Sepetys, the author of “The Fountains of Silence” (Philomel 2019) does deep research and writes historical fiction set within little-known historical events. Sepetys is considered a cross-over author meaning her books are meant for both young adults and adults.

Generalissimo Franco, the fascist dictator, has been in power since 1936 and will continue to rule until his death in 1975. Ruta Sepetys, the author of “The Fountains of Silence” (Philomel 2019) does deep research and writes historical fiction set within little-known historical events. Sepetys is considered a cross-over author meaning her books are meant for both young adults and adults.

The Matheson family is staying at the posh Madrid Castellano Hilton, once a castle. The hotel is filled with interesting characters, including Shep Van Dorn a lecherous diplomat, his reckless son Nick, the mysterious Paco Lobo and the journalist Ben. The wait staff includes the cheerful Buttons, the mean-spirited Lorenza, and the lovely Ana.

The streets are filled with Franco’s police force, called “Crows.” Any Spaniard who opposes Franco walks on thin ice. That includes Ana and her family. Her parents had been teachers and were executed by the regime for their views of education. Ana lives with her sister Julia, her brother-in-law Antonio, their infant child Lali, and her brother Rafa in the slum of Valleca. Nick Van Dorn tricks our main character, Daniel, who is a serious photographer, to visit Ana in the slum.

Not only is Ana embarrassed, it is dangerous for everyone to have Daniel’s big sleek rented Buick parked on the dirt roads along the sewage ditch of Valleca. Living on the street is Rafa’s companion, a fellow orphan, and aspiring matador, Fuga. Naïve, sweet Daniel wins over some members of the family and photographs Fuga wearing his “suit of light.” Julia is a seamstress, sewing layers of glitter and glass into the jackets and trousers of the great matadors and has borrowed this hand-me-down costume for the orphan matador. As a seamstress, “Julia’s fingers are silent narrators, embroidered with scars.”

Daniel photographs portraits of the family and arranges to give them prints. He also gets shots of the “Crows” which is terribly dangerous, a close-up of a terrified nun running with a dead baby, and eventually a shot of Franco himself. Daniel needs a great portfolio to get a scholarship to a photography school to keep him out of business school which is the only education his father will fund.

Ana and Daniel are drawn to each other, but women in Spain in 1957 cannot go on dates without a chaperone, cannot go to a restaurant or theater alone—and her family is under observation for their parents’ past. Ana says: “What similarities could he possibly see between them? Daniel can travel anywhere in the world. He is heir to an oil dynasty, lives a life of privilege, and enjoys every freedom imaginable. He can vote in an election, pray to any God of his choosing, and speak his personal feelings aloud in public.” Ana calls off the romance.

So much is amiss, including life in the orphanage where Ana’s cousin Purification works. And then Daniel’s parents adopt an infant. The Mathesons return to Texas and the story jumps to eighteen years later for its surprise ending which brings all the characters together. This reading journey is a page turner—and so informative.

Patricia Hruby Powell is the author of the award-winning Josephine; Loving vs Virginia; and Struttin’ With Some Barbecue among others. She teaches community classes at Parkland. talesforallages.com