Graphic novels can be a fantastic way to get a reluctant young adult to read. A reader of graphic novels develops visual acuity, but this takes exposure, maybe some practice. But it’s really fun. Graphic novels no longer feature just Superman and Batman “pow! bang! pop!” characters. The illustrations tend to be more universally inviting. And there are graphic novels on many topics—serious, comic, nonfiction, fiction. Here are a few.

“Child Soldier: When Boys and Girls Are Used in War” (Kids Can Press  2015) by Jessica Dee Humphreys and Michel Chikwane and illustrated by Claudia Dávila tells the non-fiction story of Michel Chikwane, a child forced into a rebel army in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The story is augmented with maps and information about child soldiers and what you can do to help end the abuse.

2015) by Jessica Dee Humphreys and Michel Chikwane and illustrated by Claudia Dávila tells the non-fiction story of Michel Chikwane, a child forced into a rebel army in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The story is augmented with maps and information about child soldiers and what you can do to help end the abuse.

The book begins with Michel arriving in the U.S.A with his mother, among other lucky refugees. The reader is given a brief history of the Congo, briefly describing the white (Belgium in this case) exploitation of its people and bountiful resources. The story is told by Michel, who says, “I played soccer, watched TV. I went to school and I daydreamed.” He explains how they made soccer balls out of crumpled paper wrapped in plastic bags and banana leaf rope. He was of the middle class, his father a human rights lawyer. His mother fed the whole neighborhood. At five years old Michel was kidnapped by a rebel army and forced to shoot his best friend. This is not easy reading, but it tells a necessary story. Many relocated refugees, now in the USA need to be seen and their stories told.

“Roller Girl” (Dial 2015) by Victoria Jameison tells the story of twelve year old Astrid whose interests diverge from those of her best friend who wants to go to ballet camp. Astrid chooses roller derby camp. It’s rough to grow apart from a best friend and find new friends and new interests. You feel Astrid’s pain and understand why she stops confiding in her mother. It’s all part of growing up. Plus you learn all about roller derby. So this is realistic fiction, with information on a sport you may have known little or nothing about.

“Roller Girl” (Dial 2015) by Victoria Jameison tells the story of twelve year old Astrid whose interests diverge from those of her best friend who wants to go to ballet camp. Astrid chooses roller derby camp. It’s rough to grow apart from a best friend and find new friends and new interests. You feel Astrid’s pain and understand why she stops confiding in her mother. It’s all part of growing up. Plus you learn all about roller derby. So this is realistic fiction, with information on a sport you may have known little or nothing about.

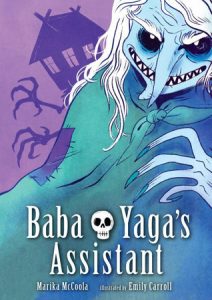

“Baba Yaga’s Assistant” (Candlewick 2015) by Marika McCoola, illustrated by Emily Carroll is fantasy fiction which embraces folklore. To escape her home and newly blended  family, teenaged Masha thinks she wants to assist the Russian folklore witch, Baba Yaga. First Masha has to get into Baba Yaga’s house, which sits atop chicken legs. Deceit rules, once she is inside the house. Masha must outsmart a bear and the witch who is serving children for dinner. This slightly dark poignant story is a fast fun read.

family, teenaged Masha thinks she wants to assist the Russian folklore witch, Baba Yaga. First Masha has to get into Baba Yaga’s house, which sits atop chicken legs. Deceit rules, once she is inside the house. Masha must outsmart a bear and the witch who is serving children for dinner. This slightly dark poignant story is a fast fun read.

These graphic novels are all high quality productions, not printed on cheap comic book paper. The color is fantastic, and the feel of the books is smooth. Try them out.

Patricia Hruby Powell is the author of Josephine: The Dazzling Life of Josephine Baker. Her young adult documentary novel Loving vs. Virginia releases in January 2017. talesforallages.com