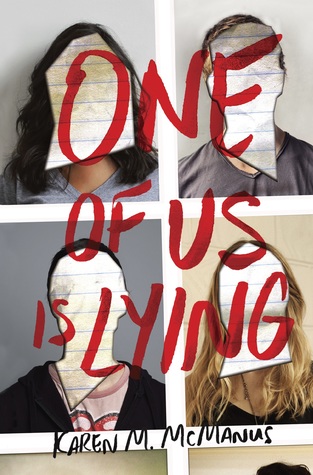

High School student, Simon, created an app called “About That,” which outs his classmates of every mistake  they commit—big and small. So everyone is afraid of him and, well, he doesn’t have a lot of friends, in Karen M. McManus’s debut novel, “One of Us Is Lying” (Delacorte 2017).

they commit—big and small. So everyone is afraid of him and, well, he doesn’t have a lot of friends, in Karen M. McManus’s debut novel, “One of Us Is Lying” (Delacorte 2017).

Simon and four of his classmates are held for detention by Mr. Avery, on charges of having their phones on them during school. The phones were planted on them. They’ve been framed.

But detention takes a terrible turn when Mr. Avery is called away and Simon starts choking, unable to breathe, and no one can find his asthma EpiPen. Simon is taken by ambulance to the hospital.

Left behind are two girls and two boys of differing demographics and descriptions.

Bronwyn, the brain, is the child of a wealthy Colombian businessman and caring mother who met at Yale where Bronwyn is set to go.

Cooper is a talented baseball player, part of the popular crowd, boyfriend to the gorgeous Keeley, with an overzealous lower middle-class sports-obsessed father, and caring mother.

Addy, a prom-queen beauty, is the child of a single-mother who has trained her daughters to catch a man. In Addy’s case that’s Jake, who’s pretty controlling. They’re equally attractive.

Nate is the guy with an alcoholic father and vanished mother, who is on probation for dealing drugs.

(I’m looking at this and thinking how the mothers here get a bad rap—or are at least subsidiary. But that’s not the story).

Simon dies in the hospital—so now what we have is a murder mystery, set near San Diego. Simon had the goods on all four of his classmates, and all four have secrets. How far would each of them go to keep his/her secret? And in spite of Simon being dead, social media keeps running a little more dirt on each of the four suspects, via “About That.” But Simon has gotten it wrong for one of the suspects. Information exists that would ruin the individual, so why hasn’t Simon, who seems to be omniscient, not have gotten that one right?

That piece of information can leave the reader/mystery-solver running down the primrose path. Throughout the whole book, you’re thinking, I’ve got it. Then a bit later, No, now I know who did it. But you’re not sure. This is why this is a best seller and being translated into 30 languages and was shortlisted for the National Book Award.

It’s being described as “The Breakfast Club” meets “Pretty Little Liars.” I think it’s better than that. It’s a page-turner supreme—not just for young adults, but for adults, too.

Patricia Hruby Powell is author of the young adult documentary novel Loving vs. Virginia and Josephine: The Dazzling Life of Josephine Baker talesforallages.com